Facilitating a workshop for the first time can seem daunting, but you can learn the facilitation skills necessary to provide a workshop experience that changes your participants, their organizations, and the world!

Maybe you’ve never facilitated a group before, or maybe you’ve only led meetings, and you sense that a workshop is something different altogether.

I agree!

The difference between meetings and workshops is immediately visible in the words. “Meetings” are where people “meet,” maybe just to give reports on things that are happening in their departments, or maybe just to hear information that the leader wants to know for sure that everyone has received.

At “workshops,” people do “work,” and sometimes it is the most important work they will do all year. A good workshop – where groups tackle and address the real and important issues they face – will change the way the team works and will impact the “bottom line” (profit, impact) within the year.

To get your started on developing your facilitation skills, let’s talk philosophically for a moment about what makes a successful workshop different from a meeting.

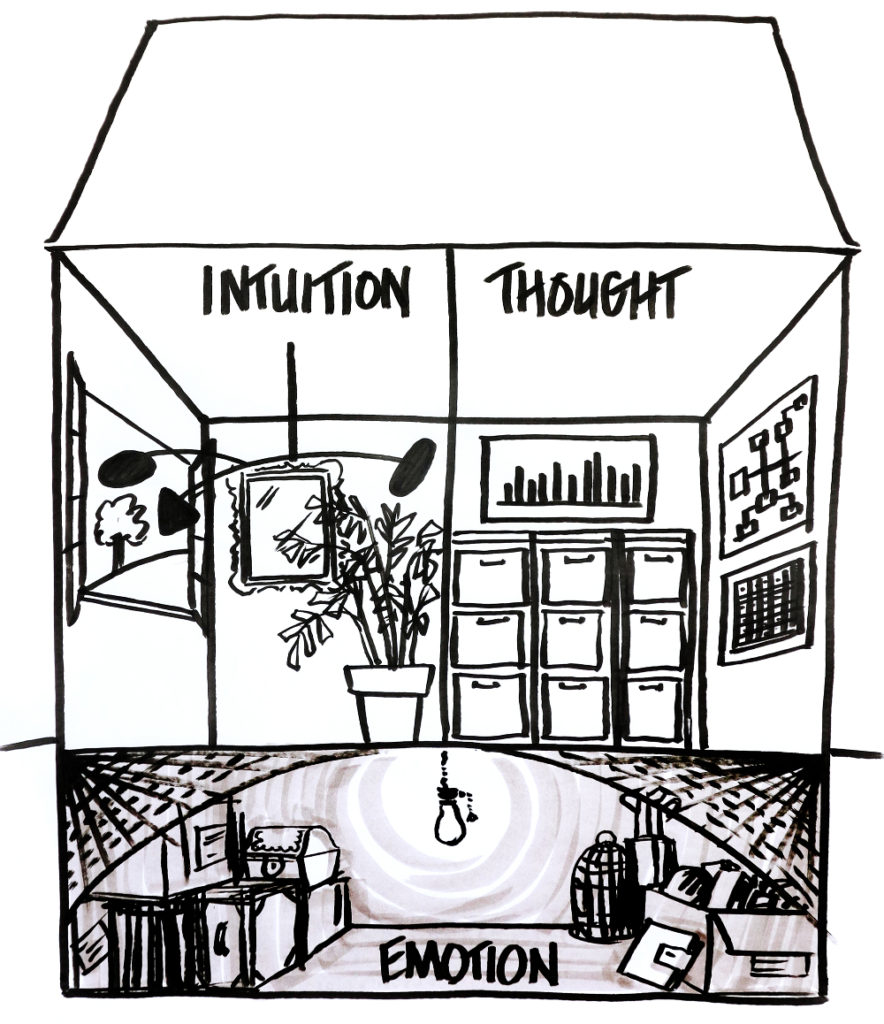

The phrase “whole mind” in the name of my company, Whole Mind Strategy Group, refers to my belief that if a workshop does not engage all three domains of the human mind, which I call “thought,” “emotion,” and “intuition,” then it probably isn’t going to make much impact on the participants or their organization. What are these three domains?

- “Thought” is the cognitive process that applies a logic we have learned to the facts we have gathered in order to draw conclusions we believe.

- “Emotion” is the bodily and transitory experience of feelings that predispose us toward different actions. (For example, anger predisposes us to attack, sadness predisposes us to withdraw.)

- “Intuition” is the capacity for awareness of the whole of a situation and of the new actions that we might take to serve a given purpose.

It may seem strange to mention emotion in this context, especially if you’re planning a workshop for a formal business or professional organization. The need for intuition may be more obvious, particularly if you’re hoping in the workshop to generate creative or innovative solutions to your team’s problem. But in most cases, you cannot get to intuition without passing through emotion first.

The above graphic shows the human mind as a house with three rooms. Thought and intuition sit next to each other on the main floor. The funny thing about this house is that you can’t go straight from thought to intuition. (You can, however, go from intuition to thought; we’ll get to that later.) The fixed assumptions and logic that prove so useful in thought make it impossible to access intuition. To access intuition, you have to pass through emotion, which is in the basement, to release your psychological hold on the things you’ve believed in the past that may no longer be useful for solving the problem at hand.

From a practical perspective, this means that when you facilitate a workshop, you have to pay attention to all three domains, and you have to structure the process to start in thought, pass through emotion, spend some generative time in intuition, and then bring the insights you find there back into thought as a new logic that can drive the team’s future action. This is the process that will unleash your team’s creativity and generate the commitment to address even the gnarliest challenges.

Now that we’ve articulated a philosophy about what a successful workshop will actually achieve, let’s talk about what you as the facilitator are actually supposed to do.

Identify the participants

Sometimes it’s obvious who needs to be at a workshop. If it’s a team development session for a team within an organization, then presumably the team members and no one else will attend. If it’s a strategy workshop for a nonprofit board, then board members will attend, and perhaps some senior level staff – though I have facilitated plenty of nonprofit strategy retreats where all board members and all staff attended.

If you’re in a position to choose the participants, then make a list of people whose behavior would need to change in order to put the workshop’s outcomes fully into practice. This includes those with the authority to make key decisions, those whose opposition might impede progress, those who will do the work of implementation, and those who will be significantly impacted by the change. Further, if an organization seeks to strengthen its relationships with external partners, then inviting those partners into its workshop may be a great way to do it.

There is a point, however, at which broad participation in a workshop prevents the group from reaching any meaningful agreement on actions coming out of the session. If the purpose of the workshop is to have diverse groups of people hear one another’s perspective, then that may not matter. However, if the workshop seeks to produce a framework for action that will guide an organization in the months to come, then lean toward inviting the people who will actually be doing that work, and include others only to the extent that their perspective is indispensable to the actual crafting of decisions and plans. Remember that there are other ways to capture the genuine opinions of the other people on your list, such as surveys, interviews, and focus groups, without inviting them into the entire workshop.

One option is to invite such external stakeholders to part of the workshop, but not to the whole thing. I often include external stakeholders on day one of a two-day workshop so that the organization’s staff can hear their perspectives directly. Then, on day two, the staff process what they’ve heard and formulate their plans for moving forward.

Choose the workshop venue

The best workshops take place in venues that change to meet the needs of the group over the course of the session. Flexibility is key. I often want to get rid of tables entirely and seat participants in movable chairs that they can reposition in large and small groupings throughout the day depending on the exercises we do. I like to have a big wall where Post-It notes and sheets of flip-chart paper can be posted and moved around as the group reorganizes their thinking. For me, the best workshop venues are rooms that are big enough for people to move around and that offer these movable chairs and an area of the wall to post new ideas.

I avoid ornate venues or spaces with very specific decor unless the decor aligns with the purpose of the workshop. One big, sunlit, properly equipped room (the flip-charts, chairs, etc. mentioned above), possibly with nearby break-out rooms if they’ll be required, and preferably with access to the outdoors if weather permits, serves as my “gold standard” for workshop facilitation. If the venue serves food, I try to make sure it is healthy and light so that participants can avoid the “food coma” that could otherwise follow lunch.

Organizations will often book their workshops in fancy wedding resorts or medieval castles or hotel ballrooms, all of which can disrupt a group’s energy and productivity – particularly if you’re not allowed to post anything on the walls. So go for a simple but spacious windowed or well-lit room with ample space and movable chairs, and let the group’s collaborative efforts be the main attraction.

Design the agenda

Our FREE 102-page workshop facilitation guide outlines a general process to move people from thought to emotion to intuition, then back to thought. It also includes specific go-to exercises that I use for each step of this journey.

But for our purposes here, let’s talk about what it might look like to spend time in each domain of the human mind as you facilitate the group through the rooms described above.

Starting in thought

Begin the meeting by welcoming participants, then present the objectives, agenda, and meeting norms you have developed. Seek their agreement to what you’ve laid out, even if only with a thumbs up. The point here is simply to align the group to the direction the workshop will take and to the structures you and they can put in place to move you along the way. The meeting norms, which I prefer to call “agreements” to signify that the participants are committing to them of their own free will, provide some guardrails for the discussions you plan to have. I typically propose agreements similar to the following:

- Respect the agenda: That doesn’t mean that the agenda won’t change, which it probably will if new issues come up that need to be addressed, but it does mean that when the facilitator says, “Take a break and come back after 20 minutes,” that the participants will come back after 20 minutes without having to be herded back in.

- Turn off devices: Of course you don’t want phones ringing or chirping in the middle of a deep, meaningful conversation. This agreement reinforced the view that this is special time you will be spending together and that it shouldn’t be disrupted.

- Be present: The main difference between a workshop and a meeting is that at a meeting it is not unusual for people to be on their computers or to step into the hallway for a conversation. Since meetings typically stay in the domain of thought, you can always get caught up on the discussion later. Not so for a workshop. At a workshop, participants “work” through a process together. The experience itself matters. For this reason, it is critical that the laptops go back in the bags, the phones get turned off, and participants commit themselves to focusing on what is actually happening in the room.

- Listen to understand: At successful workshops, participants listen to each other more deeply than they do in everyday working life, since the challenges are gnarly and the stakes are high. The facilitator should encourage participants to really listen to what their colleagues are saying rather than just spending that time framing what they want to say in response.

- Speak to be understood: This agreement has to do with making “I” statements rather than “you” statements, as in “I think, I feel, I do,” rather than “you think, you feel, you do.” We are all experts in our own experience, but not in the experience of others. Observing this agreement fosters a safe space where people can share their actual beliefs without being attacked by those who think differently.

There may be other agreements you want to add, or that the participants themselves propose. I’ve often seen “Have fun!” added to this list, which lightens the mood and thus opens the group up to more productive and meaningful conversations.

Moving into emotion

How the workshop should engage emotion will depend on the context. If it’s a strategic planning session, then the best way to bring emotion into the workshop may be to invite participants (typically in pairs or small groups) to share their highest aspirations for the organization, or share situations from the past where the organization was performing at its best. If it’s a team development session after a period of conflict or upheaval, it may be more helpful to invite participants into a place of individual reflection of the team’s potential and of new behaviors they’d be willing to adopt to help the team move forward.

There are other, more structured exercises that are helpful for signalling to participants that their emotionals are welcome in the room and that they matter as people. For example, I like an exercise from Marvin Weisbord and Sandra Janoff’s Future Search process that has participants write key events from the last thirty years on three large, butcher-block paper timelines posted on the walls. One timeline is for global events, one is for organizational events, and one is for events in the participants’ own lives. Once the timelines have plenty of content, participants form small groups to discuss what “story” each timeline tells and what the implications of that story are for the discussions they will have. While I’m a certified facilitator of the full Future Search process, I also use this particular exercise, with slight modification, in shorter workshops, and I consistently find that the inclusion of personal information and identities in the discussion leaves participants feeling valued and eager to engage more deeply.

No matter how you do it, explicitly bringing emotion into the workshop, particularly early in the agenda, creates the kind of human connection that groups need before they can tackle the gnarliest and often the most emotionally fraught challenges they face.

Moving into intuition

This is where the facilitator’s “bag of tricks” comes in, and it’s helpful for a facilitator to have a large bag of tricks. (If you plan on growing as a facilitator, keep a steady diet of new techniques and exercises.) The goal in this part of the workshop is to spark new and more holistic thinking about the matter at hand. By going through the basement of emotion, the workshop has allowed people to let go of some of their psychological attachment to existing ways of thinking and going. Now they can entertain other possibilities.

I’ve used many techniques to get people thinking differently. I’ve had participants explore alternative scenarios of the future to see what new strategies might fit the circumstances that may unfold in the years to come. I’ve had participants use craft supplies to create something representing the organization at its best. I’ve used guided visualization, long walks outdoors in pleasant surroundings, you name it! Anything that gets people thinking anew about the issues they’re facing will do the trick.

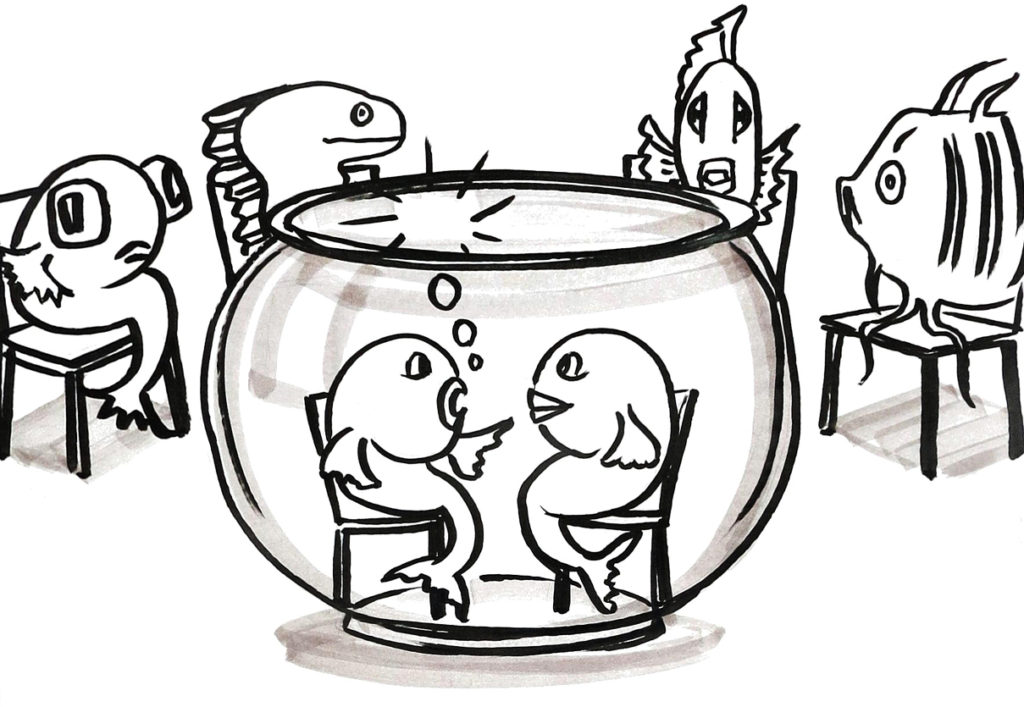

One go-to exercise that even the most novice facilitator can use is what I call the “Fishbowl” exercise. Participants sit in two concentric circles of chairs. They are divided into subgroups and each subgroup takes a turn sitting in the inner circle and having a conversation among themselves, while everyone else sits in the outer circle just listening. It’s often helpful to start with the subgroup perceived to have the most power (e.g., the executive team) so that they can model openness and honesty for others who may otherwise feel hesitant to speak their minds.

As each subgroup talks, every perspective is aired into the room so that by the end of the exercise, the group gains a holistic understanding of the situation rather than each participant or subgroup fixating only on their own concerns. This holistic view gives rise to new ideas and insights that can then be converted into new frameworks, plans, and action.

Moving back into thought

If a group doesn’t translate its new insights into a new logical construct for moving forward, then the workshop – as entertaining and enjoyable as it may have been – is unlikely to impact the team once the chairs are stacked and the flip-chart markers are put away. A group must carry its abstract new ideas back into the room of thought, since that’s where we all spend most of our working time anyway.

I see the “framework for action” – that is, the framework that expresses the new insights in an actionable form – as the key output of any workshop. This is the prize you’re after when you decide to gather up a lot of people and ask them to invest a half-day, full-day, or more together in the same room. The framework for action could take many forms. In one setting it might be a list of strategic goals to be published in a strategic plan. In another setting it might be a research agenda – a list of the topics the organization needs to learn more about before it can take the next step in addressing its biggest challenge. The key point is that the framework for action must crystallize the workshop’s deep discussions and intuitive insights into a clear logical structure that guides participants’ actions once the workshop has ended.

Communicate with participants in advance

Given the investment of time that participants will make and the depth of the conversations they’re expected to have, it makes sense to communicate clearly with them ahead of time about what will happen during the workshop. In most cases, it also makes sense to include some kind of pre-work to tune their minds to the workshop’s content. This could be a short reading or an online video explaining a new concept you’ll be working with in the workshop. It could be a questionnaire to elicit some information in advance or simply to prepare them to respond to certain questions during the session.

Sometimes it’s appropriate to share the agenda for the workshop ahead of time, but in most cases I find that less is more. While I might give the main client a more detailed description of what I have planned, I usually send participants a less detailed agenda that just lists time blocks with general names of activities. I do this for a few reasons:

- First, knowing when the breaks will be allows them to plan any calls they may need to schedule on that day.

- Second, participants typically don’t want to dig into the specifics of what will happen during the workshop; knowing that it’s scheduled and that they’ll be prepared for the content is sufficient.

- Third, the agenda will in most cases change as new issues emerge, unresolved conflicts resurface, or new information comes into view. It could be unhelpful or at least distracting for participants to have in their possession a highly detailed plan for a workshop that, as it turns out, was not the workshop that was supposed to happen.

Facilitate effectively

“Facilitate effectively” could be the most deceptively simply phrase ever written. There are people who spend their entire professional lives facilitating workshops and they still better each time they do it. So what is required to facilitate effectively? The best writing on facilitation, and in particular I’d suggest Marvin Weisbord and Sandra Janoff’s Don’t Just Do Something, Stand There and Suzanne Ghais’s Extreme Facilitation, focuses on the internal dynamics of the facilitator.

The key to being a great facilitator is not to have the cleverest activity, the best flip-chart penmanship, or the most professional demeanor when standing at the front of the room. Rather, the key to being a great facilitator is to channel whatever talents you have toward helping a group achieve its best possible outcome. This will put you in the state of mind to help the group succeed – by fostering the safety for people to share their views, by ensuring participants are engaging equitably in the discussions, and by keeping the group on task and on time.

By the way, you don’t always have to have things under control. Sometimes you won’t know what to do. It’s not unusual for a great facilitator to move a group forward by saying, “This seems to be a really important conversation, but I actually don’t know where to go from here. Does anyone have any ideas?” Invariably, the participants, who are intelligent beings in their own right, do have ideas, and by working with the facilitator they’re able to chart a way through the uncharted territory that has been discovered.

Consider the alternative, which, sadly, is also not unusual among facilitators, which is that the facilitator lumbers on with their agenda even though it no longer serves the group’s purpose. They try to project the illusion of their own competence even as the participants’ minds wander and motivation wanes.

They key to great facilitation is not to match anyone’s illusion of what a great facilitator should be, but rather to tune yourself to the highest potential of the group and to act at all times in the best interest of that potential.

If you are planning a facilitation and would like some guidance or mentorship, schedule a call with me. You can learn more about me here.

Eric Meade is a nationally recognized facilitator and an award-winning author of two books. He provides world-class facilitation to help teams and organizations address their gnarliest problems in a complex and uncertain world. He also mentors internal facilitation teams and provides facilitation skills training to young professionals and aspirating facilitators. Learn more about him, connect with him, or schedule a call to discuss your individual needs.

Artwork by Lucinda Levine, Inkquiry Visuals